In recent years, Christian author, podcaster and Focus Press online content director Jack Wilkie (hereafter JW) has written extensively on the intersection of faith and political engagement. In the fall of 2024, he compiled many of these writings into his book Christ’s Co-Rulers: Understanding Christian Political Engagement. This review aims to summarize the book’s contents and critically evaluate its biblical foundations.

I have followed JW’s work for years and deeply respect him as a skilled writer and thinker. His 2020 book Church Reset: God’s Design for So Much More is a masterpiece, powerfully calling the church to reject modern consumerism and restore God’s design for a Christ-centered family of dedicated disciples. I enthusiastically recommend it at every opportunity. However, his more recent writings on Christian political engagement – well represented in this new book – take a different approach. Rather than restoring the New Testament vison of the kingdom of God as a powerful and influential body in its own right, Christ’s Co-Rulers exchanges that biblical model for a more modern framework rooted in trust in the legitimacy and potential of earthly kingdoms and their rulers. In this move away from a restorationist framework, I found Christ’s Co-Rulers significantly more problematic. That said, it is not without valuable insights and thoughtful reflections.

Summary

The preface of Christ’s Co-Rulers clearly sets forth the book’s objective: “to address the objections and correct the popular misunderstandings of the kingdom, lay out the game plan, and exhort the church to take up her task in the realm of politics.” Throughout the various essays in the book, JW explores his understanding of how Christians can and should engage in politics and culture, seeing this involvement as an expression of Christ’s reign over all aspects of life. The book challenges the notion that any and all forms of political participation necessarily serve as a distraction from spiritual duties, instead arguing that Christians have a responsibility to influence society with the values that align with God’s kingdom.

The introduction sets the stage by rejecting the dichotomy that Christians must choose between faith and politics. JW writes, “We can win souls and elections. God can care about the church and nations. We can align with a political party and trust in Jesus.” JW emphasizes that political engagement is not idolatry but an acceptable way to spread the blessings of Christ’s rule, urging Christians to see their participation as a “good and proper exercise of a God-given gift.”

The book is then divided into three chapters, with the first chapter dedicated to answering common objections raised against political involvement. For example, the chapter begins by examining John 18:36, where Jesus states, “My kingdom is not of this world,” a passage from which many Christians have concluded that they must not engage the world using the same methods as earthly kingdoms. JW argues that while Christ’s kingdom is spiritual in origin, it manifests itself in the world, and influences the world as it grows. This influence extends, argues JW, to all areas of life, including governance. He supports this by citing biblical examples of godly individuals – such as Jonah, Elijah, or Micaiah – who engaged rulers and influenced nations.

Addressing the concern of “putting trust in princes” (Psalm 146:3), JW clarifies that Christians can participate in politics without idolizing leaders or becoming overly anxious about political outcomes. JW’s vision of political involvement, grounded in trust in God, is further established by looking to scriptural examples, such as Nehemiah sharing his concerns about Jerusalem with the king, or Paul appealing to Caesar as examples of how Christians can and should engage political rulers. JW argues that the refrain “Jesus is on his throne” is wrongly used to justify political apathy rather than being understood as a call to faithfulness. He explores other passages as well, such as Jesus’s rejection of Satan’s temptations for power, the Sermon on the Mount, and passages addressing spiritual warfare, ultimately arguing that Christians are not to avoid power, but to pursue it with humility and righteousness. In summary, Chapter 1 of Christ’s Co-Rulers seeks to systematically dismantle objections to Christian political and cultural engagement, urging Christians to actively reflect God’s authority in all aspects of life, while remaining grounded in spiritual trust and biblical principles.

Chapter 2, “A Political Kingdom” builds on the foundation laid in the first chapter, further exploring the relationship between Christianity and cultural, societal, and political engagement. The chapter begins by addressing how Christians should interpret the book of Revelation, pointing to passages such as Revelation 7:13-14 to emphasize Christ’s victory at his ascension and challenges Christians to see His kingdom as already reigning with societal implications. The discussion shifts to the church’s role in society, arguing that Christians should neither disengage from culture, nor embrace extreme and obviously problematic forms of Christian nationalism. JW instead argues for what he believes is a more balanced view, where Christians seek to advance God’s kingdom through societal and governmental influence, without conflating those efforts with nationalistic idolatry.

Chapter 3 of Christ’s Co-Rulers explores practical ways that Christians can actively make a difference in the world through righteous political engagement. JW emphasizes the importance of recognizing the times and wisely discerning the cultural shifts around us. He calls for Christians to move beyond simplistic slogans, and to boldly proclaim the truth, even when the truth results in division. JW stresses a critical commitment to both prayer and action, challenging Christians to take responsibility for the moral decline apparent in society. JW emphasizes the need to stand firm on moral truths, particularly on political matters such as abortion and gay marriage, warning against the dangers of abstention in elections. Ultimately, JW views patriotism as an expression of love for one’s neighbor. The book concludes with a thought-provoking essay which offers practical steps for Christians to positively influence their communities, churches, and families.

Overall, JW’s approach advocated in Christ’s Co-Rulers builds on a specific view of how God’s Kingdom should relate to and utilize the powers of earthly kingdoms that has become mainstream in modern evangelical Christianity. JW consistently emphasizes Christ’s ultimate Lordship over the world. While he recognizes that not all society recognizes and submits to his reign, he views Christ’s kingdom as gaining ground when little by little the structures of society begin to reflect godly values. While JW recognizes that political involvement can extend to problematic or even idolatrous extremes, he is always careful to emphasize that he is arguing for a more balanced approach.

At various points in the book, JW does attempt to engage with opposing viewpoints who take issue with Christians voting, occupying political office, or refusing to involve themselves in the public square, but the book rarely develops the logic behind such rival positions. In several instances, the book seems to reduce his opponent’s positions to flimsy bumper sticker statements, rather than confronting their arguments in the more developed forms which his opponents would actually present them. The implication seems to be that if Christians simply understood the significance of Christ’s reign the way JW does, they would reject the ridiculous arguments of his opponents and embrace the Church’s clear responsibility to mobilize for greater political influence. The most common objection against refusing earthly political activity is that he views such refusal as empty pietism, or even neo-Gnosticism. JW believes that if more believers would recognize all the good that has come because of Christian engagement in politics throughout the centuries, perhaps Christians would more readily embrace their responsibility to confront the moral issues in society through political influence.

Assessment

This book covers a lot of ground and floats a lot of ideas and arguments, some convincing and others not so much. My assessment will highlight five points of affirmation, and five quite significant reservations. If it seems like I am more critical than sympathetic, it’s probably because I am. I fear the arguments put forth in this book fall short on biblical grounds, which is especially disappointing, because this is what makes many of JW’s other writings shine.

Affirmations

Despite some significant differences, it is evident that we are strongly aligned on several key issues.

1. His Caution Against Political Idolatry

To begin, I couldn’t agree more with JW’s warning that earthly politics should not be the only or even the primary way for Christians to influence the world. Although JW’s book was compiled to make the case that involvement in politics is acceptable, he cautions against it becoming idolatrous or consuming one’s attention. In the introduction, JW cautions,

One can become inordinately focused on or involved in politics at the expense of more pressing issues… I do not believe politics is the only way we can impact the world, or even the foremost way.

Regardless of disagreements Christians may have on the question of how Christians should get involved in earthly politics, this is an important truth that must be remembered by all. Unfortunately, there are many out there who do become so enamored with party politics that it does become idolatrous, consuming all their attention. I am grateful that JW recognized this danger and cautioned Christians against it.

2. His Affirmation of the Nonviolent, Present, and Impactful Nature of Christ’s Kingdom

JW is also right to affirm Christ’s kingdom is meant to be established through peaceful means, such as evangelism and discipleship, rather than through violence or coercion. While I differ with JW on the question of how Christ’s rule is exercised and implemented in the world, with JW emphasizing Christians ruling through government, as opposed to highlighting the role of humility and suffering (more on this below in my reservations), JW is right to emphasize that Christ’s rule and influence should have a real-world impact.

In Chapter 1.1, “My Kingdom is Not of This World” JW writes,

We can’t take “not of this world” to mean “not in this world.” It literally means “not from here,” as we can see at the end of the verse. Jesus was saying that his kingdom does not originate from among wicked men, but is divine… His conquest was not going to be accomplished by letting his disciples fight for territory and control. He explicitly stopped Peter from doing that.

He goes on further to write,

So the Kingdom of Christ does not grow at the point of the sword as Islam and so many others have attempted. Its invasions are peaceful invasions, accomplished by missionaries rather than soldiers, with the message that ‘No matter how many of us you kill, we will continue sending wave after wave of Gospel proclaimers in love for your souls and obedience to Christ.

Not only that, but JW rightly emphasizes that Jesus’s reign is active, present, and universal, rather than something we merely hope for in the future (cf. Matthew 12:28-29; Revelation 11:15).

With that in mind, I appreciate JW’s emphasis on the many ways the gospel’s influence has brought about real-world blessings, such as levels of safety and prosperity “the likes of which the world has never seen” (Chapter 1.7 “Stuck in the First Century”).

While I believe JW is mistaken in the way he imagines the power of Christ’s Kingdom manifesting itself through worldly political structures, I appreciate JW’s continual emphasis that Christ’s kingdom is real and present now. While I do believe his book lacks important nuance in how Christ reigns over the world, this does not undermine the fundamental strength of his powerful affirmation of Christ’s current rule.

3. His Insistence that Christianity is More Than Private Devotion

Related to the above point, JW also rightly rejects empty pietism. JW defines “pietism” as the belief that “the Christian’s only duty is their own private walk with God” (Ch. 1.5 “The Oft Abused Sermon on the Mount”), or the reduction of Christianity to a “purely spiritual pursuit” (Ch. 2.2 “Should the Church Strive for Influence?”). His chapter on “Prayer Then Action” (Ch. 3.2) rightly highlights that both are essential aspects of faithful Christian living. His use of Queen Esther as an example (cf. Esther 4:10-17) serves as a powerful reminder of how reliance on God through prayer must lead to courageous and tangible steps of obedience.

Moreover, many of the recommendations made in the final essay in the book (Ch. 3.15, “20 Practical Ways You Can Make the World a Better Place”) strongly align with biblical wisdom, especially with their emphasis on personal discipline, spiritual growth, strong family life, and the emphasis he places on encouraging others through hospitality, encouragement, strong relationships, and service. I greatly appreciate JW’s stance against empty pietism. In fact, it is my confidence in the “real world” nature of Christianity that stands behind my primary critiques of the book (see below).

4. His Willingness to Speak Biblical Truth on Controversial Moral Issues

JW also rightly affirms godly positions on several moral issues which have been at the center of several political debates in recent years. His chapters on abortion (Ch. 3.9), gay marriage (Ch. 3.10), gambling, drugs, alcohol, and pornography (Ch. 3.11) are all excellent, laying out strong biblical arguments. In regards to these issues, I appreciate JW’s call to speak the truth boldly, even when it is controversial or divisive. This approach is consistent with Jesus’s teachings (Matthew 10:34) and Paul’s exhortation to preach the word in season and out of season (2 Timothy 4:1-4). When it comes to these moral issues, JW rightly contends that Christians have a moral obligation to address biblical truths on controversial topics (Ch. 3.6, “Divided by Politics”). While we must be careful to do this in a way that aligns with the pattern set forth by Christ, JW’s fundamental conviction that Christians must stand for truth is to be applauded.

5. His Ability to Ask Thoughtful Questions

Finally, I greatly appreciated the way JW raised some important questions. In my opinion, one of JW’s greatest strengths as an author is his ability to clearly and precisely articulate thought-provoking questions, encouraging careful examination of important biblical texts. This strength of his is evident throughout the book.

In the introduction, JW introduces the fundamental question of the book, “Is caring about politics a diversion from kingdom work? Does a Christian have to choose [between being a faithful Christian and caring about politics]?”

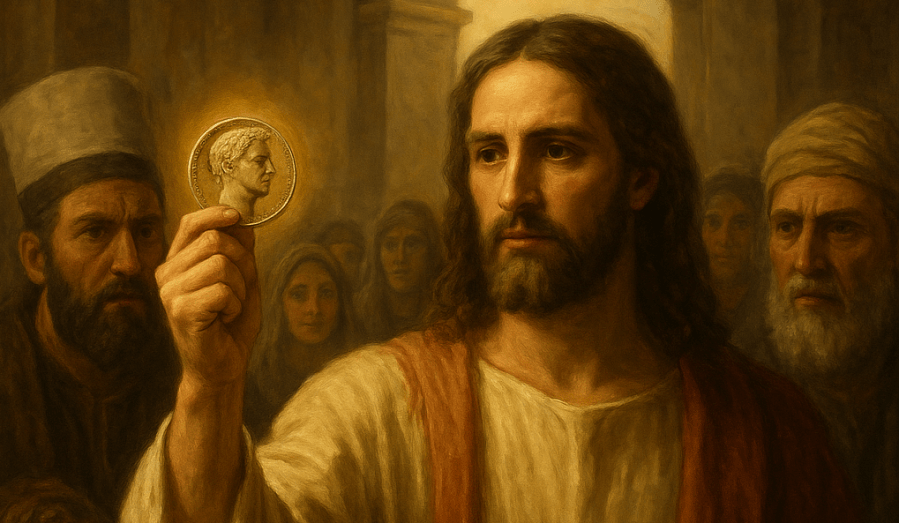

Then in Chapter 1.2 (“Are We Putting Our Trust in Princes?”) JW presses for a careful definition of what exactly it means to “put our trust in princes.” Does this mean that God is indifferent to elections and their consequences? Does this mean that we should not expect anything positive to come from the political realm? What should we do with texts from Proverbs that speak of kings ruling wisely (cf. Prov. 8:15-16; 20:28; 29:14)? What should we do with Romans 13, which speaks of God using the governing authorities as His ministers for good, or Paul’s appeal to Caesar in Acts 25:11? Was Paul “trusting in princes”?

In Chapter 1.5, (“The Oft Abused Sermon on the Mount”) JW raises the question “Where does God hold magistrates to the Sermon on the Mount?” After all, JW rightly observes, Romans 13:3-4 explicitly teaches that God appoints authorities as his ministers to execute justice against the wicked. He also raises the question about how the Sermon on the Mount should be read in light of the rest of the Bible, including the seemingly God-approved acts of violence in the Old Testament, and Jesus’s flipping of the tables in the temple.

While JW affirms that “Our war is not against flesh and blood” (Eph. 6:12; 2 Cor. 10:3-4), he raises the important question, “Do [these verses] mean that voting is a carnal weapon and that resisting Godless leadership is trying to war against flesh and blood?” (Ch. 1.6).

These are important questions that need to be asked, and I appreciate that JW’s book pushes them to the forefront of our thoughts. There is nothing wrong with asking critical questions such as “Does this text really mean what we assume it means?” or “Does God really intend for this text to be applied in this particular way in this particular circumstance?” If we really want to understand and apply the teachings of Scripture rightly, these are questions we must be asking.

With that said, I did find JW’s ways of resolving his own questions unsatisfactory in many regards. In fact, I found myself thinking of many more questions of my own as I wrestled my way through his book. But for now, I want to emphasize that I greatly appreciate the questions themselves.

Reservations

As I worked through my electronic copy of Christ’s Co-Rulers I filled almost every page with a plethora of personal notes: “Great point!” “Important truth.” “I disagree.” “Interesting thought, but needs important nuance.” “Strawman argument.” Etc. Rather than attempting to critique every aspect of the book line by line, which would require a long series of articles, I’ll touch on just a few of the most significant areas where I found JW’s book to be problematic from a biblical perspective.

1. Misreading Romans 13 and 1 Peter 2

My first reservation is quite significant. I believe that JW misunderstands and misapplies Romans 13 and 1 Peter 2, and this core difference helps explain why JW and I arrive at such different conclusions on several points.

Beginning in the introduction, JW writes “Wanting a government that punishes the wicked (Romans 13:2-4) and rewards the good (1 Peter 2:14) does not mean you don’t care about [Christ’s] kingdom.” Then in chapter 1.2 (“Are We ‘Putting Our Trust in Princes’”) JW suggests that when governments wield the sword, they are doing “what Romans 13 tells them to do.” Similarly, in chapter 2.2, JW writes that “When governments execute laws in accordance with God’s will because they are ministers of God commissioned to do exactly that (Romans 13:1-5; 1 Peter 2:13-14), it’s actually a good thing.” Other similar quotes could be cited, but over and over again, it is evident that JW understands Romans 13 and 1 Peter 2 as “commanding” or “commissioning” government authorities to rule in a particular way, that is, to use the sword to punish evil, and to reward the good.

JW is not the first to read and apply these texts in this way. But it is not correct, and it does not demonstrate a careful reading of the texts in their contexts. First, it must be observed that neither Romans 13 or 1 Peter 2 was written to governing authorities. They were written to Christians about how God uses governing authorities. This distinction is critical. Paul and Peter were not giving instructions to rulers about how they ought to govern; they were instructing Christians on how to relate to all those whom God has arranged into positions of authority.

Moreover, these passages do not present an idealized vision of government in which rulers are supposed to uphold justice in a godly manner, if only they would submit to God’s will. Rather, they describe how God sovereignly uses even wicked and rebellious rulers to accomplish His good purposes – a theme found throughout Scripture.

Paul wrote Romans under the rule of Nero, one of the most infamously cruel emperors in history. Yet Paul states in Romans 13:1 that “there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God.” Paul was certainly not suggesting that Nero was out there consciously submitting to God’s moral will. Rather he was emphasizing that even the worst rulers, such as the Roman emperor, his bureaucracy, and his military leaders, are still under His authority. This aligns with and builds on what Paul wrote earlier in the letter, in Romans 8, where Paul teaches that all things – including all kinds of wicked things that come from wicked rulers, such as tribulation, persecution, and sword – work together for the good of those who love him. This also helps explain why Paul would include these teachings as an extension of how Christians should relate to their enemies – for the Roman authorities were chief among the enemies of Christianity in Rome.

Paul goes on to say in Romans 13:3-4 that rulers “are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad” and that the ruler is “God’s servant for your good.” If taken as a prescriptive command – meaning that rulers “ought” to always punish evil and reward the good – this would contradict both history and Scripture, which repeatedly show rulers doing the opposite (e.g. Pharaoh in Exodus, Nebuchadnezzar in Daniel, and even Nero himself). Instead, Paul is making a descriptive statement, that even when rulers are corrupt, they still function under God’s providence to maintain order and accomplish his ultimate purposes.

Paul was not innovating a completely new theology of how God views and uses earthly authorities. This understanding was already established even before Paul wrote Romans. For example, in Isaiah 10:5, God calls the wicked Assyrian king “The rod of my anger” – not because Assyria was righteous, but because God was using even a sinful ruler to accomplish His will, carrying out his punishments against the wicked. Similarly, in Habakkuk 1:6, God raises up the Chaldeans, a violent and unjust people, to carry out His judgment.

Similar observations can and should be made about 1 Peter 2 :13-14 where Peter exhorts Christians to “be subject for the Lord’s sake to every human institution.” Again, as in Romans 13, this is a command directed at Christians, not rulers. The reason for this submission is not because earthly rulers govern justly, but “for the Lord’s sake,” that is, because God is ultimately in control. This theme continues in 1 Peter 2:21-23, where Peter points to Christ as the ultimate model of submission, even in the face of unjust suffering.

The fundamental flaw in JW’s interpretation is that he reads Romans 13 and 1 Peter 2 as prescriptive mandates for how governments ought to rule, rather than as descriptive truths about how God sovereignly rules through those governing authorities – whether good or evil. The idea that Christians should advocate for governments to wield the sword “as ministers of God” misunderstands the text’s purpose, and implies that these authorities would fail in their role as ministers of God if they do not respect Christ’s authority and willingly submit to his rule. If such were the case, we would expect the text to also include instructions for how Christians should wisely discern which rulers deserve to be submitted to, and which ones should be opposed. Rather than teaching Christians to make such wise discernments, the text is clear: “There is no authority except from God” (Rom. 13:1); “Be subject for the Lord’s sake to every human institution” (1 Pet. 2:13).

Nowhere do these passages command believers to shape government policies; rather they encourage Christians to trust in God’s sovereignty, even under the most wicked and oppressive rulers. We express our trust in God’s sovereignty, not by standing in opposition to wicked rulers, but by following the example of Christ, who submitted even to their most unjust cruelty (cf. 1 Peter 2:18-25).

Because JW views Romans 13 and 1 Peter 2 as prescriptive for how governments should rule, he fears the consequences Christians will endure if governments do not live up to this standard. JW writes, “Yes, elections have consequences – consequences that grow heavier all the time as postmodernism fails and we race to see whose ‘truth’ is going to win out.” Do elections have consequences? Sure. But the beauty of Romans 13 and 1 Peter 2 is that because of God’s sovereignty, we can trust that God will see to it that the consequences ultimately work out for the good of his faithful children. This distinction is crucial because it shifts the focus away from earthly political activism aimed at making governments fulfill a biblical role and instead places it where the apostles intended – on Christian faithfulness and submission, even in the midst of unjust rule.

2. The Softening of Strong Biblical Warnings

Similarly, several other passages referenced throughout the book fail to receive the careful attention and contextual examination they warrant. A prime example appears in chapter 1.2, “Are We Putting Our Trust in Princes,” where JW turns to his misunderstanding of texts like Romans 13 and 1 Peter 2 in an attempt to compartmentalize the warning of Psalm 146:3. Rather than wrestling with the psalm’s clear warning against placing trust in human rulers, JW subtly reframes it as a mere caution against having too much political anxiety. The result is a domesticated interpretation that reduces the psalm’s forceful admonition into little more than advice about maintaining a healthy balance between political engagement and personal spiritual disciplines like Bible study, prayer, and church involvement.

Psalm 146:3 warns against putting trust in princes – human political leaders – in those areas where our trust rightly belongs to God alone. For instance, in 1 Samuel 8, when the Israelites were dissatisfied with God’s rule, they demanded a king to fight their battles for them. To ask for a king to fight their battles expressed a lack of trust in God’s kingship and their belief that a human ruler could provide greater security and success in battle. God’s response through Samuel warned them that a human king would lead to oppression and disappointment, but they “trusted in princes” anyway.

Later in Israel’s history, King Ahaz of Judah faced the threat of invasion by Syria and Israel. Rather than trusting in the Lord, Ahaz turned to Assyria for protection, offering silver and gold from the temple as a tribute (2 Kings 16:7-9; Isaiah 7). Isaiah warned Ahaz to trust in the LORD’s deliverance, but Ahaz chose political alliances over faith. This pattern of misplaced trust continued when Judah faced a threat from Assyria. Rather than relying on God, they looked to Egypt’s military for help. Isaiah rebuked them for this misplaced trust (2 Kings 17:4-6; 2 Chronicles 36:13). Similarly, Ezekiel warned that Egypt was a broken reed and would fail those who leaned on it (Ezekiel 29:6-7).

Within this Old Testament context, it becomes clear that “putting your trust in princes” involves far more than simply becoming overly anxious about the political powers or failing to maintain healthy balance between political engagement and spiritual devotion – though it certainly would include these concerns. At its core, this phrase refers to the deep error of relying on earthly rulers for security, deliverance, or victory in battles that ultimately belong to the Lord. It includes forming alliances with worldly powers in the hope of achieving greater success against God’s enemies. Yet this is precisely the trajectory JW’s book encourages when it urges Christians to engage in various culture wars by partnering with political structures and earthly authorities – a move that, according to Scripture, repeatedly leads to compromise and disappointment.

Other examples abound. For instance, JW appeals to Proverbs to illustrate “wise rulership,” treating those maxims as a handbook for modern politicians rather than recognizing that the Proverbs ultimately point to the Messiah himself – the perfect King whose wisdom and justice stand in stark contrast to every human ruler’s folly. Likewise, JW invokes the story of David and Goliath to argue that Christians need not always follow the Sermon on the Mount’s teaching on enemies – overlooking, however, that David’s victory is less a model for militant resistance than a testament to God’s deliverance through humble and confident faith. In each case, JW reframes biblical accounts meant to exalt God’s unique sovereignty as templates for worldly power struggle, rather than as demonstrations of the cross-shaped authority entrusted to Christ and his followers.

3. True Authority is Found in Sacrifice, Not Dominion

A third reservation is that JW’s tends to sideline the cross as the centerpiece of Christ’s authority. By suggesting in Chapter 1.4 (“Jesus Denied Power”) that Jesus’s post-resurrection exaltation vindicates the pursuit of worldly power, JW downplays what Scripture repeatedly affirms: the cross itself is “the power of God” (1 Corinthians 1:18-25). Throughout the New Testament, Jesus’s voluntary self-emptying and crucifixion are held up as the highest demonstration of true authority (Philippians 2:5-11). “The way of the cross” is not merely a prelude to glory but the very wisdom and might of God. Christ himself taught that genuine greatness is found not in lording it over others “as the Gentiles do” (Mark 10:42-45) – but in humble service and sacrificial love.

This misstep becomes especially apparent in JW’s reading of Revelation (Chapter 2.1, “Reading Revelation Right”). JW argues that because believers “reign with” the exalted Christ – going “from under the altar” (Revelation 6:9-11) to “enthroned with him” (Revelation 20:4) – Christians ought to exercise authority over the nations. Yet he overlooks the book’s stark contrast between imperial power and the Lamb’s paradoxical rule. Although Jesus bears the Lion’s title, He exercises his authority as the slain lamb (Revelation 5:6), revealing that his dominion is won by self-sacrifice, not by the sword.

Revelation’s imagery of the four horsemen (Conquest, War, Famine, and Death) and the beasts of chapters 11 and 13 vividly portray the world’s coercive, violent authority (cf. Revelation 11:7-8; 13:7). By contrast, those who share in the Lamb’s blood – and “do not love their lives even to death” – overcome evil through suffering, not force (Revelation 12:10-11). Their victory lies in following the Lamb “wherever he goes,” even following him to his death (Revelation 14:4; 12:11), rather than by forging earthly alliances.

Far from endorsing a co-rulership with Babylonian-style regimes, Revelation invites us into a kingdom that is sharply contrasted with earthly kingdoms, where true power is perfected in weakness, and where the slain Lamb reigns supreme over every throne of this world.

4. The Unresolved Tension of Coercive Power in the Peaceful Kingdom

A fourth reservation concerns JW’s failure to fully grapple with the implications of Christ’s peaceful kingdom. In chapter 1.1, JW begins on a promising note, rightly emphasizing that “[Jesus’s] conquest was not going to be accomplished by letting his disciples fight” and that “the kingdom of Christ does not grow at the point of the sword.” However, he quickly pivots away from this foundational truth and shifts the focus from advancing the gospel through peaceful means to advancing it through earthly political strategy. This creates a tension he never resolves: if Christ’s kingdom is not advanced by violence, how can Christians justify using the inherently coercive mechanism of state power to further it?

The heart of the issue is that every government policy is ultimately enforced by the power of the sword – by law, punishment, and, in extreme cases, the threat of death. JW never explains how this reality squares with the nonviolent principles upon which Christ built his kingdom. The Sermon on the Mount explicitly teaches practices like turning the other cheek, loving one’s enemies, and refusing to resist evil with violence (Matthew 5:38-48). These are not abstract ideas but commands meant to be lived out by Christ’s disciples. While JW raises thoughtful questions about these teachings in Chapter 1.5 (“The Oft Abused Sermon on the Mount”) – such as whether the Sermon applies to governing authorities or how it relates to Old Testament violence – he sidesteps the more pressing issue: how can followers of Jesus faithfully live out these commands while using political force against their enemies?

Certainly, there is nothing wrong with wrestling with questions about the meaning and proper application of the Sermon on the Mount, but raising them must never be used as a way to evade obedience to their intended meaning, or to dismiss those teachings as optional, only to be applied in certain situations where it seems wise in our own eyes to do so. Even if the Sermon on the Mount isn’t a blueprint for public policy, it remains the teaching of Christ himself about how his disciples should live in his kingdom. JW’s unwillingness to wrestle with how Christians can reconcile participation in systems that rely on coercion and violence while remaining faithful to the commands of Christ himself is a major omission. Faithful interpretation of the Sermon of the Mount does not mean only asking whether it applies to governments – it means asking how Christ’s radical call to peace and enemy-love must shape every sphere of a Christian’s life, including how they relate to political powers. To treat the Sermon as merely an ideal, or as optional in certain contexts is to risk undermining the intended radical nature of what it means to follow Christ.

5. The Portrayal of Gospel Centered Engagement as Neo-Gnosticism

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of Christ’s Co-Rulers is its repeated misrepresentation of non-partisan or non-power-seeking engagement as passive, ineffective, or even heretical. JW consistently frames the refusal to pursue secular political power as a form of “pietism,” “neo-Gnosticism,” or simply “doing nothing.” This framing appears most clearly in Chapter 1.2 (“Are We Putting Our Trust in Princes”) where he likens non-political Christians to someone trapped on a rooftop during a flood, refusing to get into a boat because “God will save me.” The implication is clear: those who decline participation in earthly politics are neglecting real-world responsibility in favor of naïve, escapist faith.

But where does this idea come from? Certainly not from Jesus. Christ had numerous opportunities to leverage earthly political power – whether in the wilderness with Satan, in the crowds who wished to make him king, or in his trial before Pilate – and he rejected every one of them. Would JW suggest that Jesus, in refusing those paths, was “doing nothing”? Nor does this view arise from the example of the early church. The apostles did not agitate for governmental reform or align themselves with state power, yet they turned the world upside down through the proclamation of the gospel, suffering, and self-sacrificial love. The book of Acts is not a story of passivity – it’s a story of a radical, Christ-shaped political engagement: an alternative form of politics rooted in the kingdom of God, not the kingdoms of men.

It is important to clarify here what I mean by “politics.” If politics refers only to the partisan system that continually contends to control the coercive power of the state, then yes, Christians can and should abstain. But if we define politics more broadly, as the patterns, values, and powers that influence and shape human society, then faithful discipleship to Jesus is deeply political. The church is not merely a religious body – it is a polis, a city set on a hill, an alternative and rival kingdom, called to teach and display an alterative way of life. The language of the New Testament is filled with political vocabulary – kingdom, gospel, law, justice, Lord, Messiah – not as metaphors, but as redefinitions of those terms. The gospel doesn’t call Christians to abandon politics but to practice a different kind of politics, one rooted in the reign of Christ, not Caesar. Abstaining from partisan strategies or the pursuit of political power is not an act of retreat, but an act of trust – a public display of confidence in the power of God’s way of organizing human life through Christ-like sacrificial love, obedience, and righteousness.

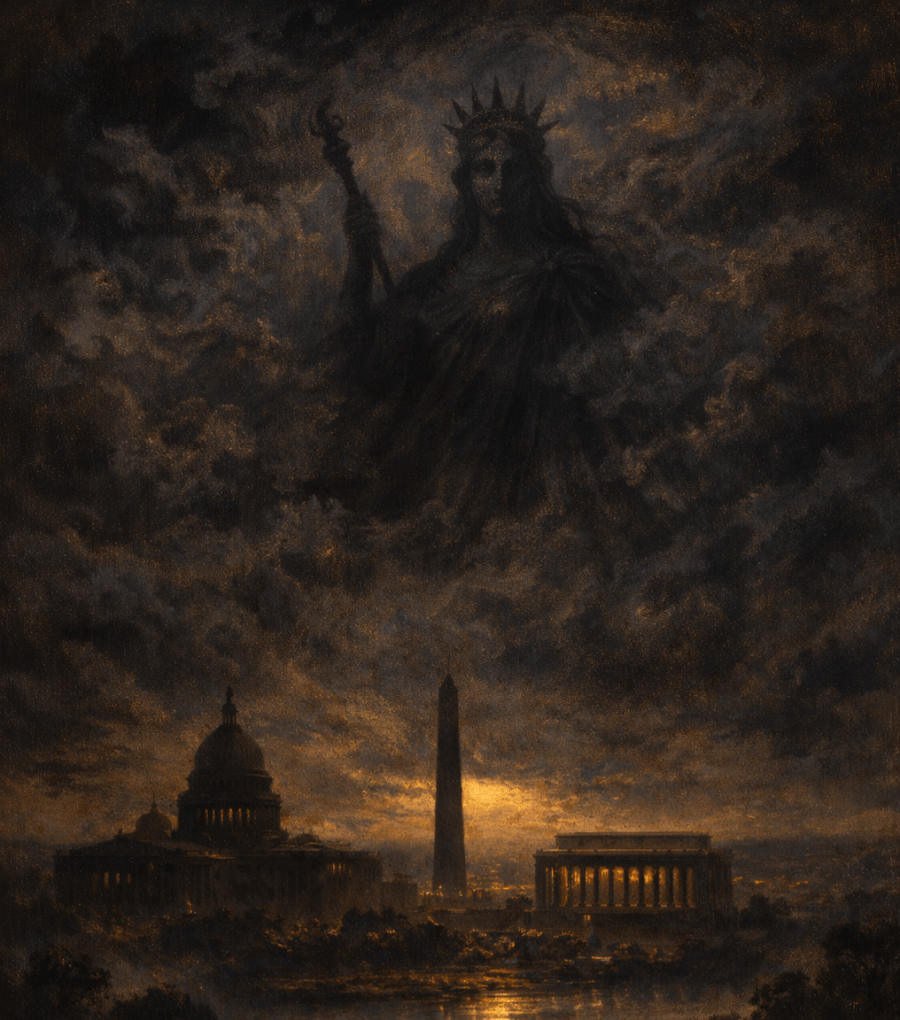

In truth, JW’s assumption that avoiding earthly political involvement equals inaction reflects not a biblical worldview, but a pagan one. In ancient paganism, both spiritual and earthly powers were tools to manipulate the world for desired outcomes. From that perspective, refusing to use the levers of political power when that power is within reach would seem like doing nothing. Like so much of modern Christianity, the influence of this pagan worldview can be traced back to the fourth-century emperor Constantine. After Constantine’s alleged conversion, Christians suddenly found themselves with access to significant state power. Within a few decades, the Church had become the official religion of the Roman Empire and following Rome’s collapse, a dominant state power for centuries to come. Catholic theologians, such as Eusebius and Augustine, interpreted this newfound power as a gift to the church by God. By means of political power, it was believed that the Church “militant and triumphant” would conquer the nations for Christ. Christ’s Co-Rulers represents a modern revival of this Constantinian legacy, which conflates worldly influence with faithfulness, and political victories with gospel success. In this way, the book embraces a paradigm that has shaped much of post-Constantinian Christianity, rather than restoring the radical, countercultural politics of the New Testament church.

Throughout the teachings and examples found in the New Testament, the kingdom of God does not advance through coercion, violence, or political maneuvering, but through the power of the gospel. To reject entanglement with earthly politics is not to withdraw from the world – it is to practice politics on God’s terms, trusting in His methods. Rather than ruling with Caesar, Jesus chose the cross.

The flipside of this concern is that JW’s rhetoric undermines the real-world power of the gospel. To be fair, JW explicitly denies this in the introduction, where he writes, “I do not believe political involvement is the only way we can impact the world, or even the foremost way.” He also ends the book with a list of practical ways to change the world – most of which do not involve earthly politics at all. These are commendable acknowledgments. But they are undercut by the broader thrust of his argument, in which he repeatedly characterizes gospel-centered engagement as inadequate. By labeling gospel-focused Christians as guilty of “empty pietism” or “neo-Gnosticism,” JW suggests – I believe unintentionally – that proclaiming Christ and living out Christ’s commands is somehow insufficient for combating evil in the world.

So which is it? Is preaching the gospel, baptizing the nations, and teaching them to obey the commands of Jesus the most powerful way to change the world – or is it “doing nothing”? If the gospel is truly “the power of God for salvation” (Romans 1:16), and if Christ’s way of overcoming evil is through doing good, and if love and truth are indeed effective in making a difference in the real world, then there is no basis for the charge of pietism. The problem is not that JW denies the gospel’s power with his words – it’s that he undermines it with his assumptions. And those assumptions – about earthly political action being the default mode of cultural engagement – go largely unexamined throughout the book.

In the end, JW must choose. If he truly believes the gospel is powerful, he cannot continue to belittle those who trust in it rather than the sword. But if he dismisses their convictions as impractical and irresponsible, he will inevitably shift the weight of Christian hope away from Christ and onto Caesar. And in so doing, he unwittingly redefines the very nature of the kingdom he claims to defend.

Final Thoughts

I began this essay by expressing my disappointment that Christ’s-Co Rulers departs from the restoration of New Testament Christianity. I said this because it is clear that the imitation of the way of Christ and the early church is not at the heart of this book. While the Lordship of Christ is certainly a prominent theme in the book, the implementation of his reign is framed in the tools of earthly kingdoms rather than in the way of the cross. The arguments rely heavily on dubious uses of proof texts, often divorced from their context, rather than on careful exegesis.

What is most striking is the near absence of the way of Christ as revealed in the Gospel – the path of suffering, submission, and self-giving love. The teaching of Christ and the apostles are mentioned but rarely allowed to shape the book’s vision in any substantive way. In the end, Christ’s Co Rulers does not call the church to imitate Christ in his path to the cross, but to mirror the power structures of the world. In that sense, a more fitting title might be Babylon’s Co-Rulers, for it aligns more closely with the logic of earthly kingdoms than with the kingdom of God.

That is not the restoration the church needs. It is a rebranding of the Constantinian compromise. If we are to be faithful to the kingdom Jesus proclaimed, we must reject the sword and embrace the cross – not just as a doctrine, but as the way we live, love, and yes, even engage in politics.

And yet, the vision of restoration is not entirely lost either. Christ’s Co-Rulers still invites us to carefully examine Scripture and to consider the real-world implications of Christ’s reign. Though the book is deeply flawed in its approach, perhaps it will nonetheless stir a renewed hunger in the church – one that leads us back to the beautiful, powerful, and world-reversing reign of Christ, embodied in the lives of faithful Christians.